6) Git for good programming practices¶

Related material:

- Main basis (with many thanks) for this ipynb: https://swcarpentry.github.io/git-novice/

- Related nice reference: http://swcarpentry.github.io/git-novice/reference

- Additional Git reference: https://git-scm.com/docs

- https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2

- https://gist.github.com/trey/2722934

Version control with git¶

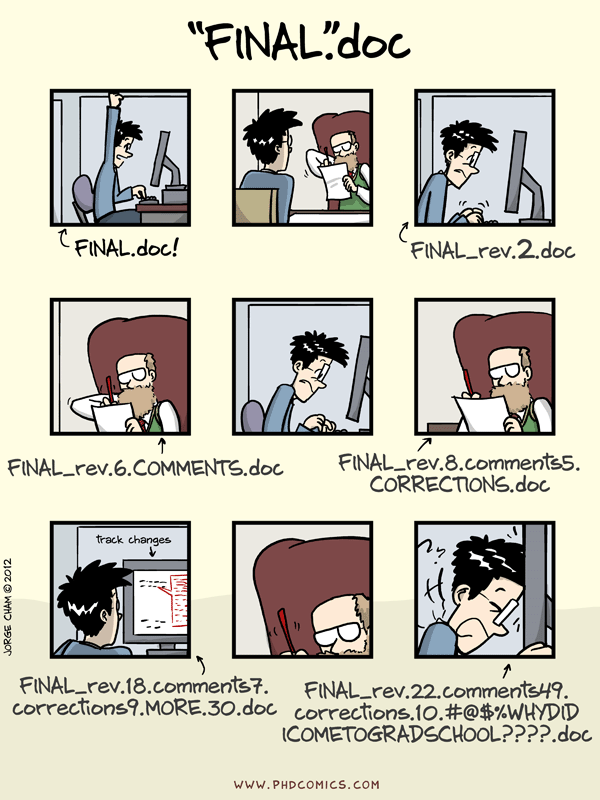

Git is an extremely useful and broadly adopted version control system. Every save copies of files with different names as you work on them to enable going back to older versions?

“Piled

Higher and Deeper” by Jorge Cham, http://www.phdcomics.com

“Piled

Higher and Deeper” by Jorge Cham, http://www.phdcomics.com

Git (and other version control software) avoids saving many almost-identical versions of files and then having to sort through them. It makes it very easy to store incremental changes and then compare them. When writing programs, this is especially useful as you might temporarily have to break some functionality while extending it; wouldn’t it be nice to make a separate “branch” to work on that, and merge it back when the new functionality is complete?

This is such a common problem that multiple version control tools have been created. Git is the most common. It becomes especially helpful when there are multiple people that want to work on the same project/file.

Git is not to be confused with GitHub; GitHub is an online host (website) for projects which interfaces with git. It is extremely helpful for sharing code, managing projects, and team project development. We will be using both.

Some visuals of what git can do for you:¶

Save changes sequentially:

Make independent changes to the same file:

Merge changes: If there are conflicts, you will have a chance to review

them.

The entire history of saved states (commits) and the metadata about them make up a particular git repository. These repositories are saved on individual machines, but can easily be can be kept in sync across different computers, facilitating collaboration among different people. Repositories do not need a central server to host the repo (the common shorthand for repository). Thus, git repos are described as distributed.

When first using Git on a machine¶

Below are a few examples of configurations we will set as we get started with Git:

- our name and email address,

- what our preferred text editor is,

- and that we want to use these settings globally (i.e. for every project).

On a command line, Git commands are written as git verb options,

where verb is what we actually want to do and options is

additional optional information which may be needed for the verb. So

here is how Dracula sets up his new laptop:

$ git config --global user.name "Vlad Dracula"

$ git config --global user.email "vlad@tran.sylvan.ia"

The user name and email you set will be associated with your subsequent Git activity, which means that any changes pushed to GitHub, BitBucket, GitLab or another Git host server.

Line Endings¶

As with other keys, when you hit Return on your keyboard, your computer encodes this input as a character. Different operating systems use different character(s) to represent the end of a line. (You may also hear these referred to as newlines or line breaks.) Because Git uses these characters to compare files, it may cause unexpected issues when editing a file on different machines.

Although it is beyond the scope of this lesson, you can read more about this issue on on this GitHub page.

You can change the way Git recognizes and encodes line endings using the

core.autocrlf command to git config. Thus, the following

settings are recommended:

On macOS and Linux:

$ git config --global core.autocrlf input

And on Windows: ~~~ $ git config –global core.autocrlf true ~~~

We will be interacting with GitHub and so the email address used should be the same as the one used when setting up your GitHub account. If you are concerned about privacy, please review GitHub’s instructions for keeping your email address private.

If you elect to use a private email address with GitHub, then use that

same email address for the user.email value, e.g.

username@users.noreply.github.com replacing username with your

GitHub one. You can change the email address later on by using the

git config command again.

Dracula also has to set his favorite text editor, following this table:

| Editor | Configuration command |

|---|---|

| Atom | $ git config --global core.editor "atom --wait

" |

| nano | $ git config --global core.editor "nano -w" |

| BBEdit (Mac, with command line tools) | ``$ git config –global core.editor “bbedit -w”` ` |

| Sublime Text (Mac) | $ git config --global core.editor "/Applicatio

ns/Sublime\ Text.app/Contents/SharedSupport/bin/

subl -n -w" |

| Sublime Text (Win, 32-bit install) |

“`` |

| Sublime Text (Win, 64-bit install) |

|

| Notepad++ (Win, 32-bit install) |

|

| Notepad++ (Win, 64-bit install) |

bbar -nosession -noPlugin”`` |

| Kate (Linux) | $ git config --global core.editor "kate" |

| Gedit (Linux) | $ git config --global core.editor "gedit --wai

t --new-window" |

| Scratch (Linux) | $ git config --global core.editor "scratch-tex

t-editor" |

| Emacs | $ git config --global core.editor "emacs" |

| Vim | $ git config --global core.editor "vim" |

It is possible to reconfigure the text editor for Git whenever you want to change it.

The four commands we just ran above only need to be run once: the flag

--global tells Git to use the settings for every project, in your

user account, on this computer.

You can check your settings at any time:

$ git config --list

You can change your configuration as many times as you want: just use the same commands to choose another editor or update your email address.

Git Help and Manual¶

If you forget a git command, you can access the list of commands by

using -h and access the Git manual by using --help :

$ git config -h

$ git config --help

Let’s make a Git repo!¶

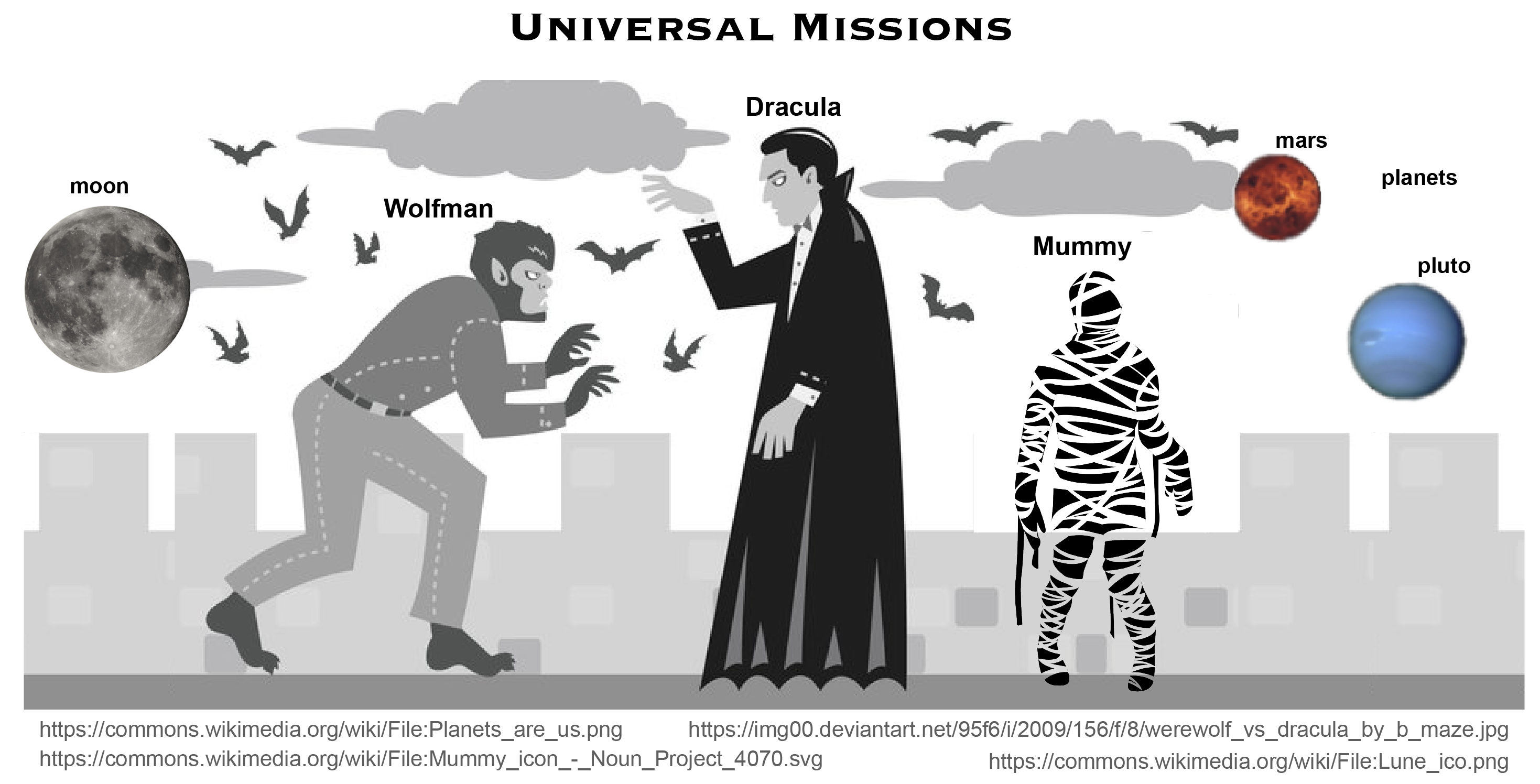

We will make a repo for a project Wolfman and Dracula are working on, investigating if it is possible to send a planetary lander to Mars.

motivatingexample

First, let’s create a directory in Desktop folder for our work and

then move into that directory:

$ cd ~/Desktop

$ mkdir planets

$ cd planets

Then we tell Git to make planets a repository (where Git can store

versions of our files):

$ git init

Note: that git init will create a repository that includes

subdirectories and their files—there is no need to create separate

repositories nested within the planets repository, whether

subdirectories are present from the beginning or added later. Also, note

that the creation of the planets directory and its initialization as

a repository are completely separate processes.

If we use ls to show the directory’s contents, it appears that

nothing has changed:

$ ls

But if we add the -a flag to show everything, we can see that Git

has created a hidden directory within planets called .git:

$ ls -a

. .. .git

Git uses this special sub-directory to store all the information about

the project, including all files and sub-directories located within the

project’s directory. If we ever delete the .git sub-directory, we

will lose the project’s history.

We can check that everything is set up correctly by asking Git to tell us the status of our project:

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)

If you are using a different version of git, the exact wording of

the output might be slightly different.

Correcting git init Mistakes¶

USE WITH CAUTION!¶

To undo accidental creation of a git repo (e.g. did init when in the

Desktop directory, instead of after changing directory to planets), you

can just remove the .git within a current directory using the

following command:

$ rm -rf moons/.git

But be careful! Running this command in the wrong directory, will remove

the entire Git history of a project you might want to keep. Therefore,

always check your current directory using the command pwd.

Tracking Changes¶

Let’s create a file called mars.txt within the folder planets

that contains some notes about the Red Planet’s suitability as a base.

We’ll use vim to edit the file; this editor does not have to be the

core.editor you set globally earlier.

$ vim mars.txt

Type the text below into the mars.txt file:

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

mars.txt now contains a single line, which we can see by running:

$ ls

mars.txt

$ cat mars.txt

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

If we check the status of our project again, Git tells us that it’s noticed the new file:

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

mars.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

The “untracked files” message means that there’s a file in the directory

that Git isn’t keeping track of. We can tell Git to track a file using

git add:

$ git add mars.txt

and then check that the right thing happened:

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: mars.txt

Note: You can add individual files by adding them by name, or any

changes listed after typing status (new/modified/deleted files) by

typing git add .

Git now knows that it’s supposed to keep track of mars.txt, but it

hasn’t recorded these changes as a commit yet. To get it to do that, we

need to run one more command:

$ git commit -m "Start notes on Mars as a base"

[master (root-commit) f22b25e] Start notes on Mars as a base

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 mars.txt

When we run git commit, Git takes everything we have told it to save

by using git add and stores a copy permanently inside the special

.git directory. This permanent copy is called a

commit (or

revision) and its short

identifier is f22b25e. Your commit may have another identifier.

We use the -m flag (for “message”) to record a short, descriptive,

and specific comment that will help us remember later on what we did and

why. If we just run git commit without the -m option, Git will

launch vim (or whatever other editor we configured as

core.editor) so that we can write a longer message.

Good commit messages start with a brief (< 50 characters) statement about the changes made in the commit. Generally, the message should complete the sentence “If applied, this commit will …”.

If you want to go into more detail, add a blank line between the summary line and your additional notes. Use this additional space to explain why you made changes and/or what their impact will be.

If we run git status now:

$ git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

it tells us everything is up to date. If we want to know what we’ve done

recently, we can ask Git to show us the project’s history using

git log:

$ git log

commit f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b

Author: Vlad Dracula <vlad@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 09:51:46 2013 -0400

Start notes on Mars as a base

git log lists all commits made to a repository in reverse

chronological order. The listing for each commit includes the commit’s

full identifier (which starts with the same characters as the short

identifier printed by the git commit command earlier), the commit’s

author, when it was created, and the log message Git was given when the

commit was created.

Where Are My Changes?¶

If we run ls at this point, we will still see just one file called

mars.txt. That’s because Git saves information about files’ history

in the special .git directory mentioned earlier so that our

filesystem doesn’t become cluttered (and so that we can’t accidentally

edit or delete an old version).

Now suppose Dracula adds more information to the file.

$ vim mars.txt

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

When we run git status now, it tells us that a file it already knows

about has been modified:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: mars.txt

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

The last line is the key phrase: “no changes added to commit”.

We have changed this file, but we haven’t told Git we will want to save

those changes (which we do with git add) nor have we saved them

(which we do with git commit).

If you want to review your changes before saving them. We do this using

git diff. This shows us the differences between the current state of

the file and the most recently saved version:

$ git diff

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index df0654a..315bf3a 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1 +1,2 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

+The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

The output is a series of commands for tools like editors and patch

telling them how to reconstruct one file given the other:

- The first line tells us that Git is producing output similar to the

Unix

diffcommand comparing the old and new versions of the file. - The second line tells exactly which versions of the file Git is

comparing;

df0654aand315bf3aare unique computer-generated labels for those versions. - The third and fourth lines once again show the name of the file being changed.

- The remaining lines are the most interesting, they show us the actual

differences and the lines on which they occur. The

+marker in the first column shows where we added a line.

Now to commit:

$ git commit -m "Add concerns about effects of Mars' moons on Wolfman"

$ git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: mars.txt

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Why did we get that note?

$ git add mars.txt

$ git commit -m "Add concerns about effects of Mars' moons on Wolfman"

[master 34961b1] Add concerns about effects of Mars' moons on Wolfman

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

Git insists that we add files to the set we want to commit before actually committing anything. This allows us to commit our changes in stages and capture changes in logical portions rather than only large batches.

For example,suppose we’re adding a few citations to relevant research to our thesis. We might want to commit those additions, and the corresponding bibliography entries, but not commit some of our work drafting the conclusion (which we haven’t finished yet).

To allow for this, Git has a special staging area where it keeps track of things that have been added to the current changeset but not yet committed.

Staging Area¶

If you think of Git as taking snapshots of changes over the life of a

project, git add specifies what will go in a snapshot (putting

things in the staging area), and git commit then actually takes

the snapshot, and makes a permanent record of it (as a commit). If you

don’t have anything staged when you type git commit, Git will prompt

you to use git commit -a or git commit --all.

Only do this if you are certain you know what will go into the commit,

at least by checking git status first!

The Git Staging Area

Let’s watch as our changes to a file move from our editor to the staging area and into long-term storage. First, we’ll add another line to the file:

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

$ git diff

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index 315bf3a..b36abfd 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1,2 +1,3 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

+But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

Now let’s put that change in the staging area and see what git diff

reports:

$ git add mars.txt

$ git diff

There is no output: as far as Git can tell, there’s no difference between what it’s been asked to save permanently and what’s currently in the directory. However, if we do this:

$ git diff --staged

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index 315bf3a..b36abfd 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1,2 +1,3 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

+But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

it shows us the difference between the last committed change and what’s in the staging area.

Let’s save our changes:

$ git commit -m "Discuss concerns about Mars' climate for Mummy"

[master 005937f] Discuss concerns about Mars' climate for Mummy

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

check our status:

$ git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

and look at the history of what we’ve done so far:

$ git log

commit 005937fbe2a98fb83f0ade869025dc2636b4dad5

Author: Vlad Dracula <vlad@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 10:14:07 2013 -0400

Discuss concerns about Mars' climate for Mummy

commit 34961b159c27df3b475cfe4415d94a6d1fcd064d

Author: Vlad Dracula <vlad@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 10:07:21 2013 -0400

Add concerns about effects of Mars' moons on Wolfman

commit f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b

Author: Vlad Dracula <vlad@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 09:51:46 2013 -0400

Start notes on Mars as a base

Paging the Log¶

When the output of git log is too long to fit in your screen,

git uses a program to split it into pages of the size of your

screen. When this “pager” is called, you will notice that the last line

in your screen is a :, instead of your usual prompt.

- To get out of the pager, press Q.

- To move to the next page, press Spacebar.

- To search for

some_wordin all pages, press / and typesome_word. Navigate through matches pressing N.

Limit Log Size¶

To avoid having git log cover your entire terminal screen, you can

limit the number of commits that Git lists by using -N, where N

is the number of commits that you want to view. For example, if you only

want information from the last commit you can use:

$ git log -1

commit 005937fbe2a98fb83f0ade869025dc2636b4dad5

Author: Vlad Dracula <vlad@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 10:14:07 2013 -0400

Discuss concerns about Mars' climate for Mummy

You can also reduce the quantity of information using the --oneline

option:

$ git log --oneline

- 005937f Discuss concerns about Mars' climate for Mummy

- 34961b1 Add concerns about effects of Mars' moons on Wolfman

- f22b25e Start notes on Mars as a base

Directories¶

Two important facts you should know about directories in Git.

- Git does not track directories on their own, only files within them. Try it for yourself:

$ mkdir directory

$ git status

$ git add directory

$ git status

Note, our newly created empty directory directory does not appear in

the list of untracked files even if we explicitly add it (via

git add) to our repository. This is the reason why you will

sometimes see .gitkeep files in otherwise empty directories. Unlike

.gitignore, these files are not special and their sole purpose is to

populate a directory so that Git adds it to the repository. In fact, you

can name such files anything you like.

If you create a directory in your Git repository and populate it with files, you can add all files in the directory at once by:

git add <directory-with-files>

To recap, when we want to add changes to our repository, we first need

to add the changed files to the staging area (git add) and then

commit the staged changes to the repository (git commit):

The Git Commit Workflow

Author and Committer¶

For each of the commits you have done, Git stored your name twice. You are named as the author and as the committer. You can observe that by telling Git to show you more information about your last commits:

$ git log --format=full

When committing you can name someone else as the author:

$ git commit --author="Vlad Dracula <vlad@tran.sylvan.ia>"

Exploring History¶

As we previously saw, we can refer to commits by their identifiers. You

can refer to the most recent commit of the working directory by using

the identifier HEAD.

We’ve been adding one line at a time to mars.txt, so it’s easy to

track our progress by looking, so let’s do that using our HEADs.

Before we start, let’s make a change to mars.txt:

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

An ill-considered change

Now, let’s see what we get.

$ git diff HEAD mars.txt

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index b36abfd..0848c8d 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1,3 +1,4 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

+An ill-considered change.

which is the same as what you would get if you leave out HEAD (try

it). The real goodness in all this is when you can refer to previous

commits. We do that by adding ~1 (where “~” is “tilde”, pronounced

[til-d*uh*]) to refer to the commit one before HEAD.

$ git diff HEAD~1 mars.txt

If we want to see the differences between older commits we can use

git diff again, but with the notation HEAD~1, HEAD~2, and so

on, to refer to them:

$ git diff HEAD~2 mars.txt

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index df0654a..b36abfd 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1 +1,4 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

+The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

+But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

+An ill-considered change

We could also use git show which shows us what changes we made at an

older commit as well as the commit message, rather than the

differences between a commit and our working directory that we see by

using git diff.

$ git show HEAD~2 mars.txt

commit 34961b159c27df3b475cfe4415d94a6d1fcd064d

Author: Vlad Dracula <vlad@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 10:07:21 2013 -0400

Start notes on Mars as a base

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..df0654a

--- /dev/null

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

+Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

In this way, we can build up a chain of commits. The most recent end of

the chain is referred to as HEAD; we can refer to previous commits

using the ~ notation, so HEAD~1 means “the previous commit”,

while HEAD~123 goes back 123 commits from where we are now.

We can also refer to commits using those long strings of digits and

letters that git log displays. These are unique IDs for the changes,

and “unique” really does mean unique: every change to any set of files

on any computer has a unique 40-character identifier. Our first commit

was given the ID f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b, so let’s

try this:

$ git diff f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b mars.txt

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index df0654a..93a3e13 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1 +1,4 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

+The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

+But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

+An ill-considered change

That’s the right answer, but typing out random 40-character strings is annoying, so Git lets us use just the first few characters:

$ git diff f22b25e mars.txt

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index df0654a..93a3e13 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1 +1,4 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

+The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

+But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

+An ill-considered change

All right! So we can save changes to files and see what we’ve changed—now how can we restore older versions of things? Let’s suppose we accidentally overwrite our file:

We will need to manufacture our own oxygen

git status now tells us that the file has been changed, but those

changes haven’t been staged:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: mars.txt

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

We can put things back the way they were by using git checkout:

$ git checkout HEAD mars.txt

$ cat mars.txt

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidity

As you might guess from its name, git checkout checks out (i.e.,

restores) an old version of a file. In this case, we’re telling Git that

we want to recover the version of the file recorded in HEAD, which

is the last saved commit. If we want to go back even further, we can use

a commit identifier instead:

$ git checkout f22b25e mars.txt

$ cat mars.txt

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: mars.txt

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Notice that the changes are on the staged area. Again, we can put things

back the way they were by using git checkout:

$ git checkout HEAD mars.txt

Don’t Lose Your HEAD¶

Above we used

$ git checkout f22b25e mars.txt

to revert mars.txt to its state after the commit f22b25e. But be

careful! The command checkout has other important functionalities

and Git will misunderstand your intentions if you are not accurate with

the typing. For example, if you forget mars.txt in the previous

command.

$ git checkout f22b25e

Note: checking out 'f22b25e'.

You are in 'detached HEAD' state. You can look around, make experimental

changes and commit them, and you can discard any commits you make in this

state without impacting any branches by performing another checkout.

If you want to create a new branch to retain commits you create, you may

do so (now or later) by using -b with the checkout command again. Example:

git checkout -b <new-branch-name>

HEAD is now at f22b25e Start notes on Mars as a base

The “detached HEAD” is like “look, but don’t touch” here, so you

shouldn’t make any changes in this state. After investigating your

repo’s past state, reattach your HEAD with git checkout master.

It’s important to remember that we must use the commit number that

identifies the state of the repository before the change we’re trying

to undo. A common mistake is to use the number of the commit in which we

made the change we’re trying to get rid of. In the example below, we

want to retrieve the state from before the most recent commit

(HEAD~1), which is commit f22b25e:

Git Checkout

So, to put it all together, here’s how Git works in cartoon form:

Simplifying the Common Case¶

If you read the output of git status carefully, you’ll see that it

includes this hint: ~~~ (use “git checkout – …” to discard changes in

working directory) ~~~ As it says, git checkout without a version

identifier restores files to the state saved in HEAD. The double

dash -- (optional) separates the names of the files being recovered

from the command itself. Without it, Git might try to use the name of

the file as the commit identifier (but I haven’t had this problem).

The fact that files can be reverted one by one tends to change the way people organize their work. If everything is in one large document, it’s hard (but not impossible) to undo changes to the introduction without also undoing changes made later to the conclusion. If the introduction and conclusion are stored in separate files, on the other hand, moving backward and forward in time becomes much easier.

Explore and Summarize Histories¶

Exploring history is an important part of git, often it is a challenge to find the right commit ID, especially if the commit is from several months ago.

Imagine the planets project has more than 50 files. You would like

to find a commit with specific text in mars.txt is modified. When

you type git log, a very long list appeared, How can you narrow down

the search?

Recall that the git diff command allow us to explore one specific

file, e.g. git diff mars.txt. We can apply a similar idea here.

$ git log mars.txt

Unfortunately some of these commit messages are very ambiguous e.g.

update files. How can you search through these files?

Both git diff and git log are very useful and they summarize a

different part of the history for you. Is it possible to combine both?

Let’s try the following:

$ git log --oneline --patch mars.txt

You should get a long list of output, and you should be able to see both commit messages and the difference between each commit.

Tagging¶

If there is a particularly important commit, e.g. a new version of a program, you can add an identifier to your commit (that is, just after committing). There are two types of tags. A “lightweight” tag is as simple as:

$ git tag v0.1-lw

This tag simply points to a particular commit and then can be used for checking out a branch instead of the alphanumeric string given to the branch.

More useful is the annotated tag:

$ git tag -a v1.0 -m "my version 1.0"

Annotated tags are stored as full objects in the Git database. They’re checksummed; contain the tagger name, email, and date; have a tagging message; and can be signed and verified with GNU Privacy Guard (GPG) (cryptographically signed). It’s generally recommended that you create annotated tags so you can have all this information, and then it is a full bookmark of the state.

If desired, read more about tagging here.

We’ll continue our discussion of Git at the next class!